Introduction

Welcome to the HARVEY Maps blog on all things Navigation.

Here you will find insightful articles, useful tips and interesting stories on navigating outdoors, written by HARVEY Ambassador, Nigel Williams.

The Navigation Blog is changing! Take a look at the new HARVEY Blog Space here.

March 2 2021 - What 3 Words & OS Locate

March 2021 - NNAS, Navigate with Confidence

December 2 2020 - Navigating 2021 and beyond

December 1 2020 - Tips on navigating in a winter white out

November 2020 - Cognitive navigation and GPS

September 2020 - MapRun

July 2020 - Navigation research

March 2020 - Contours - round or over, how to do a rough calculation

December 2019 - Using the 3rd dimension for navigation

November 2019 - Contours - the 3rd Dimension

July 2019 - Contours Part 2 - further anecdotes of mapping elevation

July 2019 - Contours Part 1 - some historical anecdotes

May 2019 - National Map Reading Week

March 2019 - Global warming

February 2019 - Winter clothing tips

January 2019 - Winter Munroing kit

December 2018 - Be Avalanche Aware

November 2 2018 - Altimeters

November 1 2018 - It's Getting Dark

October 2018 - The psychology of getting lost

March 2 2021

What 3 Words & OS Locate

by Nigel Williams

In 2019 Scottish Mountain Rescue released a statement to say they will always try to work with any information that helps to locate a casualty, however, in the end they translate it into a grid reference in order to plan a safe route to the casualty location.

With a minimal phone signal and the "share" icon both apps can send your location by text. With W3W someone receiving the text can paste it into their W3W app and ask the system to navigate to you. It then operates like a satnav offering a straight line direction (which may be hazardous in the hills). However, it is particularly useful in an urban setting when you won't have a map or a grid reference is not appropriate, remembering that a 6 fig grid represents a 100m square.

OS Locate is my go to app in the hills. It is more of a navigational tool than W3W as it gives me an altitude and has a compass. If I'm on a path which is on the map half way up a hill I only need the altitude to work out my exact position where the relevant contour crosses the path. This is quicker than faffing with a grid reference which may require unfolding the map etc. And I can use it anywhere in the world. The compass is a useful back up, especially with the incidence of reverse polarity - usually caused by the compass rubbing against the phone in a pocket.

Whilst the smart phone appears to be the simple answer to everything it is a nightmare to work if the screen gets wet, or the batteries get cold or run out or it gets dropped and damaged. Not forgetting other rarer possibilities of GPS interference and spoofing. So, perhaps all this technology is really just a back up to the good old map and being able to read a grid reference. However, as a bare minimum I could get myself off the hill with either of them if I lost my map and compass and they are the easiest and quickest way of getting help.

Return to introduction

March 1 2021

NNAS - Navigate with Confidence

by Nigel Williams

Grid references, quantifying bearings and the importance of magnetic variation come from the military around WW2, when one wrong number could lead to shelling ones own troops. It is more about map reading and static plotting, as opposed to on the move navigation. Numbers are merely a means of communication. Today we use navigation for recreation and most people follow paths, yet much of the teaching reflects an 80 year old approach. This may stem from geography lessons as map reading is required for exams. However, I suspect this gets mistaken for navigation in the minds of many pupils and has a negative effect on their confidence to navigate.

By 1945, Scouts and the 3 armed services cadet forces were being taught map reading. The Duke of Edinburgh's Award started in 1956, Ten Tors in 1959 and Mountain Leadership Awards in 1964. A decade later orienteering is established in the UK, HARVEY Maps are producing ground breaking cartography for orienteering maps and the British Orienteering Federation (now British Orienteering) is developing a successful coaching scheme. I think at the time the view was that orienteering had little to do with the map reading requirements of the established organisations. The maps were different and lacked the numbers which were viewed as essential to teaching. The participants ran, wore odd clothing and belonged to a club; none of which are necessary to take part these days. The established organisations seem to have shown little interest in investigating in the teaching methodology and amazing navigation efficiency and skill of orienteers. We now know that the basic cognitive ingredients required for navigation are the same regardless of the map and terrain so navigation in any context will develop navigation confidence and should not be dismissed.

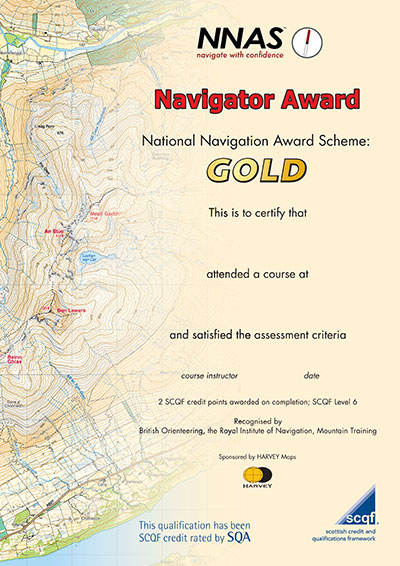

In 1994 Peter Palmer was a keen orienteer, coach and school teacher running Duke of Edinburgh. He could see how orienteering mapping and teaching methodology could help the pupils gain confidence with hill navigation. He established the National Navigation Award Scheme (NNAS) which has been supported by the Royal Institute of Navigation and other bodies including Mountain Training.

The NNAS is now a Scottish charity. It is the only organisation concerned with recreational navigation that has come after orienteering. Although it sees the orienteering map as a valuable tool in teaching the skills, the aim is to teach broader non-competitive recreational navigation with traditional OS and HARVEY map scales.

The Navigator Awards use Bronze, Silver and Gold levels. These are aimed at anyone interested in learning and developing navigation skills in the wider countryside. Participants can start at any level; the content is carefully structured to provide progressions and develop confidence. Each level has a 12 hour practical contact time, usually a weekend. All the Tutors have to attend a one day Tutor Award course to familiarise them with the teaching methodology (orienteering being the only other body to do this). As a result, the Navigator Awards have been approved by the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) and are listed on the Scottish Credits and Qualifications Framework so they can be recognised within education and training settings. Outdoor education that can actually be formally credited. It is not just education groups that use the NNAS; rescue teams, the Army and RAF cadets, some Duke of Edinburgh's Award and Scouting and Girlguiding groups also use the NNAS. It provides a bench mark of navigation skills. In addition, the Tutor course is recognised as a valuable piece of continuing professional development by all the UK professional mountaineering bodies.

It appears that the Navigator Awards align closely with the emerging science as to how humans would have naturally developed navigation skills long before maps. Many of the scientific papers talk about the importance of confidence with navigation which is a focus of the NNAS teaching methodology and is reflected in their recently adopted strapline, 'Navigate with Confidence'.

From the beginning, the NNAS has been fortunate to have been supported by HARVEY Maps with a shared aim of wanting to help people learn to navigate, enjoy maps and outdoor adventures. Sue Harvey has been the Chair of the NNAS Board of directors and HARVEY Maps has published all 3 books that support the NNAS scheme and produces a range of other navigation teaching resources.

For more information see www.nnas.org.uk

Return to introduction

December 2 2020

Navigating 2020 and beyond

by Nigel Williams

The book "Wayfinding" by Michael Bond sparked much thought about how we learn to navigate and wayfind. As a toddler, frequently the first experience of being lost is in a supermarket or shop. Our spatial awareness has not yet developed to enable us to even point in the direction of the car park. Yet, over time, in the outdoors, we can develop our cognitive map to help us operate in the hills in winter, supressing the fear of being lost as we develop confidence in both remote terrain and our ability to use the tools of navigation. A prime example of this development is evident in the central London cabbies who spend 4 years learning "The Knowledge", 60,000 streets and over 100,000 point of interest. They never use a GPS but develop an unusually large hippocampus, the part of the brain that manages our map memory and cognitive navigation capabilities. Neuroscientists are planning further studies of cabbies neurological powers over the next few years.

Some recent experiments indicate that the earliest humans may at one time have been able to detect magnetic fields that gave them a sense of direction similar to some animals and birds today. It may be a lost capability. Do some people still have it though - for example water diviners?

There is now a considerable amount of research to suggest that men and women are equally capable of navigating. They just do it differently. In one experiment, navigating a route using a 3D map, women completely outshone men, whereas the men outshone the women with the 2D traditional map (invented by men of course). It seems women use landmarks and visual clues, noticing their surroundings more than men. Men tend to be more aware of distance and direction information. Actually the reality is that most of us use a mixture of both but may have a bias one way or the other. The future may see a much wider range of mapping being available to suit different people and purposes.

I covered GPS in a recent blog, but as we reach the final Brexit outcome the UK has already left the European Space Agency, responsible for the European GPS satellite system Galileo. We still have recreational access to it on our devices but access to the high end military capabilities may be limited in future. The government now plans to develop a next generation UK GPS system of satellites. A few other nations have a GPS satellite system limited to their country only. Our reliance on these systems is fundamental to our everyday lives and their vulnerability is becoming a serious issue. Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) capability that used to refer to nuclear weapons is now emerging as a space strategy, hence the rapid development of space defence units in the major countries of the world.

On a more cheerful note, I'm sure most people are familiar with the term "desire line" when referring to footpaths that cut out a zigzag, particularly going downhill for example.

Well, Tristan Gooley, the guru of natural navigation has just come up with the term "Smile Path": a well worn curved path around obstacles like fallen trees, large puddles, etc.

Here's hoping we can all get back to navigating around the hills in 2021.

Return to introduction

December 1 2020

Tips on navigating in a winter white out

by Nigel Williams

A compass direction operates in two dimensions on a flat surface, only 2/3 of the information we need to navigate effectively in whiteout.

A winter whiteout is when, in poor weather, the sky and ground become one so there is no horizon line and it is impossible to make out the lay of the land just in front of you. It can be very intimidating, especially around ridges, steep avalanche prone slopes and cornices (lips of compacted snow that overhang cliffs and outcrops). Without anything to aim a compass bearing at one can drift significantly off course and the eyes and mind play tricks, especially if a strong wind is blowing snow diagonally across our route or into our face. Forget the old idea of throwing snow balls in front of you to aim on - it doesn't work.

Careful route planning is essential. Try to design a route using objectives that are changes in contour information which can provide physical feedback. For example, a straight line bearing takes us diagonally downwards across a slope for 600m to reach flat ground. Using pacing and feeling the change in the contour spacing enables us to be reasonably accurate about our position. Further confirmation can be obtained by asking companions to walk away in different directions to the limit of visibility and observe if they appear to be level, above or below. This idea can also help gauge the slope aspect (direction the slope is facing).

If there is more than one navigator and compass in a group, walking accurately on a bearing can be managed by working as a team. Once the objective, bearing, distance and expected feel of the ground is agreed, a confident navigator goes out in front about 5 - 10 metres ahead, doing their best to follow the bearing on their compass. The next person behind follows with the same bearing on their compass and steers the front person - "left a bit", "on", "right a bit", "on", often shouting in the wind. With the rest of the team close behind the second person everyone is moving.

The lead person follows the instructions drifting back onto the bearing. The lead person ideally is also counting the paces although others could do this, (the person shouting the instructions can't count paces as well).

If there is only one compass or confident navigator then it can be done by sending an individual to the limit of visibility then directing them left or right onto the bearing, then the group walks to them and the process is repeated. This is a depressingly slow and cold process.

Return to introduction

November 2020

Cognitive navigation and GPS

by Nigel Williams

London cabbies usually spend around 4 years memorising the A-Z map of central London, they call it "Knowledge". They can go between any two places in any direction and are able to work out alternatives if there are delays. They don't use GPS. MRI scans of their brains as they learn the Knowledge shows that they develop a larger than usual hippocampus.

Research into the cognitive impact of using a GPS for navigation goes back to the early 2000s. One experiment asked two sets of people to navigate a route through a built-up area. One set were equipped with maps and compasses the other following the route on a GPS. On arrival at the destination point the navigation tools were removed and they were asked to back track the route from memory. The map and compass users managed the task quickly with few mistakes. The GPS users had difficulty in achieving the task.

Following the dot or arrow on the screen meant that they had barely observed any landmarks around them nor were they particularly conscious of key decision-making points along the route.

Further studies have demonstrated that habitual use of the GPS fails to develop navigation decision making skills but more fundamentally, it fails to develop our cognitive navigation skills in the hippocampus. Furthermore, it appears that the part of the brain required to interact with the GPS, the caudate nucleus (the same part of the brain that works when interacting with video games), silences the hippocampus. It is easy to see which way society seems to be heading.

As we get older the hippocampus deteriorates as we become more sedentary. Scientists are unravelling this decline clearly observed in Alzheimer's sufferers. However, there is good evidence that we need to stimulate the hippocampus to help protect it.

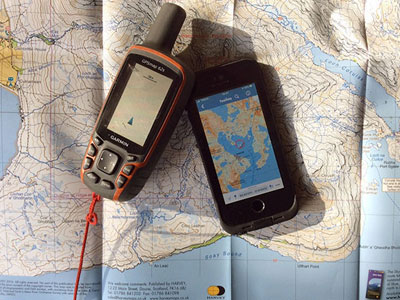

There is a choice as to how we interact with our GPS/phone on the hill. There is a continuum - at one end we can follow the dot and let the GPS control us. At the other end we can exercise our spatial awareness, observation and decision-making skills with a map and just use the GPS to confirm a decision after it has been made, in that scenario we control the GPS.

In between those two ends are a range of levels of integration using navigation tools combined with our spatial awareness and decision making skills. Examples might be using a screen map without the GPS function or navigating from a paper map and taking regular position checks from the GPS.

The aim ought to be to integrate the tools in order to benefit both navigation efficiency and spatial knowledge acquisition.

Return to introduction

September 2020

MapRun

by Nigel Williams

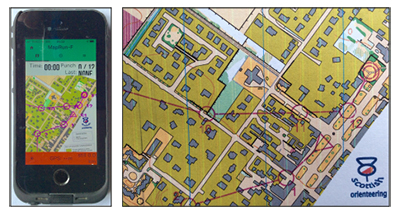

Over 30 countries are using it. Orienteering clubs across the UK are mapping and putting courses online on a weekly basis. There are over 130 across Scotland. Check your local orienteering club website. See www.scottish-orienteering.org for more information and to download the maps.

When it comes to navigation generally there seems to be either a paper or GPS mentality. We hear of an increase in mountain rescues where the only navigation tool has been the phone. Of course those same people may have needed help if they had relied solely on a paper map and compass, but possibly they would not have gone out in the first place if they had no skills or confidence with map and compass. Map Run offers the option of learning to use both together which is how most outdoor professionals now operate, partly because it allows them more head space for interaction and managing safety of clients knowing the GPS as a backup, will pin point them in seconds.

In the last blog I briefly talked about the need to develop the brain's navigation processes and that navigation requires decision making and confidence. It also requires observation skills.

Most people will have used Satnav in the car to find their way to an unfamiliar place and then felt unable to retrace the route without Satnav. This is because the brain has not been able to create a mental map from observing and recording multiple land marks and the sequence of direction changes etc. Driving safely is also a distraction and an indication that navigation tends to need our full attention.

Experiments have been done with people on foot following GPS mapping and tracking on an unfamiliar back street urban route. Unexpectedly at the end they have the GPS and mapping disabled and have to retrace their steps from memory. Same thing is done with other individuals who used a paper map. They proved to be more successful in retracing their route because they had to constantly relate the map and ground, observing landmarks and their relationship to each other, which built up a mental map.

This demonstrates that total reliance on the GPS is less effective at activating and developing the neurological navigation processes. Secondly, that online learning to navigate (which has been talked about in the outdoor sector quite a bit during the lockdown) has only limited use and that we need to engage with the outdoor environment and terrain in order to develop the neurological navigation processes and confidence.

Return to introduction

FREE UK delivery

FREE UK delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch