Terrain confidence and spatial awareness

by Nigel Williams

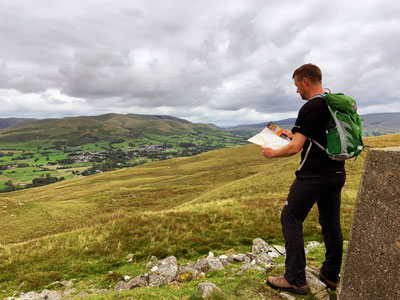

Terrain confidence is easily observed through watching people make their early excursions onto unfamiliar surfaces or environments, such as venturing off the path into rough stony ground or through heather, or early experiences of walking on snow. We may observe it in the level of their efficiency, speed and smoothness of movement over the ground and their reduced ability to look around at the landscape and route ahead to take in valuable navigational and wayfinding information. We sometimes see it in basic route choice and decision making at a path junction where there can be a bias towards the easiest looking path which often has the least detailed navigational information. Research using eye tracking software suggests that self-confidence about our motor abilities is more likely to influence our gaze and focus, potentially drawing us into modifying our decision-making.

Inevitably, if on the move, our gaze is going to be limited and decisions will be made hastily. When we stop, we can observe more information. Novices often attempt to make a navigation decision by long periods of staring at their maps and limiting their gaze to the direction they are facing when they stopped and failing to take in 360º of information.

Terrain and decision-making confidence is also linked to our early years' development of spatial navigation experiences. "Sea Hero Quest" was a huge project supported by Alzheimer's UK to try to measure peoples' level of spatial navigation ability, it's decline with age, and whether it could provide an early indication of dementia. Essentially it was an on-line game which sought non-verbal spatial navigation information. It ran for nearly 5 years from 2017 in 38 countries involving 4.3 million people. There is no longer public access to the game but analysis of the data is creating many more areas of research and producing some fascinating insights which could have relevance to how we might adapt our approach to teaching navigation based on evidence rather than inherited methods.

This seems to makes sense, city dwellers are limited by the road network, their commute is often very local and their services are also close by so they generally travel less with fewer route options. Those brought up in the countryside can experience more varied terrain (making them more terrain confident) and have more short cuts and route decision-making options and have to travel further for school, work and services.

Journeying and exploring is an important aspect of developing spatial awareness for young people, it also appears that our early years' experience has the greatest and longer lasting impact on our level of spatial awareness throughout our life. (Good evidence based arguments for outdoor education).

Added to that, information analysis has also shown that on average men have a slightly better spatial awareness over women. Also, on average, people educated to tertiary level demonstrated better spatial awareness than those educated to secondary level. The gender difference may be influenced by our social norms. Sons are generally allowed or encouraged to go off and explore with their mates whereas there is a tendency to be more protective of daughters thus limiting their opportunity to explore to the same extent.

We are better at navigating in topologically similar environments to what we grew up in and early years exploration has the biggest and longest lasting influence on our spatial awareness. All this has relevance to the who, how, what, where and why of our approach to teaching the skills of navigation and the importance of confidence building. Taking a young city dweller into the countryside may need more attention to developing terrain confidence and a steadier use of teaching progressions. Terrain confidence increases our capacity to observe and gather navigational and wayfinding information and therefore supports navigation decision making. Lastly, this may also point to some of the hidden underlying reasons for the increasing number of MR callouts for walkers lost, overdue or missing.

References:

Explaining World-Wide Variation in Navigation Ability from Millions of People: Citizen Science Project Sea Hero Quest - Spiers HJ, Coutrot A, Hornberger M. 2021

Landmark-dependent Navigation Strategy Declines across the Human Life-Span: Evidence from over 37,000 Participants - Greg I. West, Patei, Antoine Coutrot, Michael Hornberger, Veronique D. Bohbot, Hugo J Spiers. 2022

Entropy of city street networks linked to future spatial navigational ability - Coutrot, A., Manley, E., Goodroe, S., Gahnstrom, C., Fiomena, G., Yesiltepo, D., Dalton, R.C., Wiener J.M., Hölsher, C., Hornberger M., Spiers, H. J. 2022

Fork in the road: How self-confidence about terrain influences gaze behaviour and path choice - Vinicius da Eira Silva and Daniel S. Marigold. 2023

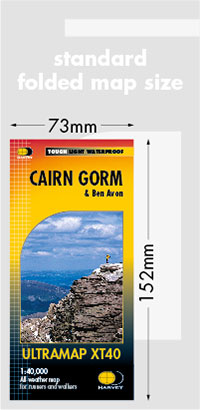

- If you are looking for some information on the basics of navigating with a map, then take a look at Outdoor Discovery, Active Exploration with a Map - suitable for all levels of navigation, and includes several easy to follow and fun activities.

Return to the Navigation Blog

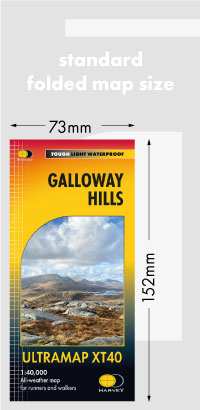

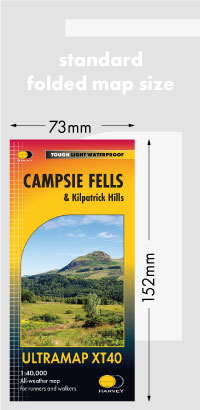

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch