Buying a compass

by Nigel Williams

Despite the fact that these days most people have an electronic device to assist with navigation, rescue teams are reporting an increase in the number of people becoming lost in the hills and estimate that poor navigation accounts for around 50% of call outs.

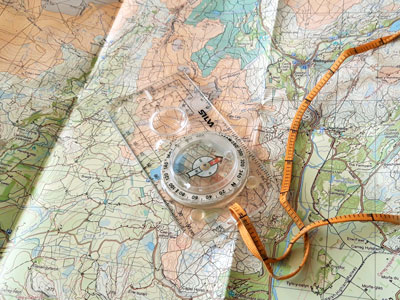

A compass is essentially a simple scientific instrument and it can save your life, but more likely save you from the embarrassment of being disorientated and late home. There are many recreational compasses on the market and the price range is considerable from about £5 to £70, but in general you pay for what you get. Silva and Suunto are the two most reliable makes with the widest range of models.

The variables of cost are the base plate size, having a magnifying glass within the base plate and the range of markings and scales on the base plate. The longer the base plate the more accurately one can aim at things when navigating across country. A magnifying glass can often help one see detail that may be partially hidden by writing on the map for instance. Longer base plates will have a wider range of scales.

More significant to the cost though is the steadiness, magnetised strength and reliability of the floating needle in the housing capsule.

The liquid in the capsule is also a cost factor, water is cheaper than something akin to white spirit which has a slightly thicker, more oily texture and has a much lower freezing point, around -25º, so good in winter and it steadies the needle movement if you are walking cross country on a bearing. The needle balances on a fine pin and the south (white) end of the needle is fractionally longer than the north (red) end to counter the north end being pulled towards the ground. Finally, there is the sealing of the capsule with no air bubbles. So, there is quite a bit of super accurate manufacturing involved.

The most expensive recreational compasses, around £60 plus, have a plastic disk instead of a needle which sits on a small magnetic block on the pin. This provides a much bigger surface area in contact with the white spirit which dampens the movement of the needle making it settle very quickly and one can walk or run with it quite accurately across country without the needle wobbling all over the place. Preferred by orienteers and professional outdoor instructors.

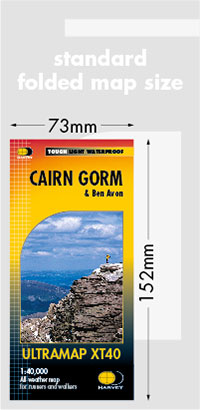

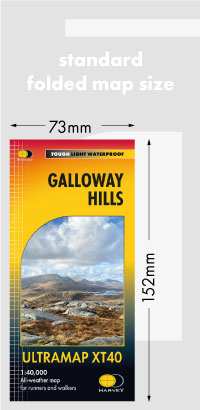

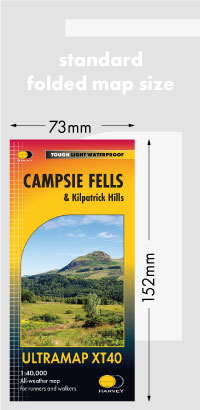

For most people walking or biking well-marked paths only using the compass for map setting and deciding which path to take at a junction, not really intending to walk cross country legs in remote terrain, then a short base plate is adequate; expect to pay around £20 - £25 for a good model. Anyone aspiring to be more adventurous should consider a longer base plate, expect to pay around £30 - £35. If you are a HARVEY map user then there is only the Silva Expedition Mk 4 with the 1:40,000 scale on it.

The manufacturing of compasses has largely moved to China, and recently there seems to be a higher incidence of bubbles developing in the capsules. Sometimes they can appear on the higher tops in a low pressure weather system but disappear back down at sea level. Once a bubble is about 5mm across it is going to impact the needle accuracy. Most manufacturers will replace the compass for free up to 5 years from manufacture.

- If you are in need of a compass then we stock a great range of items and other useful navigation equipment, suitable for all levels of navigation.

- For the perfect lanyard to go with your compass, the HARVEY Map - Measure - Go! scale bar laces double up to make measuring distance easy! Available in two scales, 1:25,000 scale markings (red) and 1:40,000 scale markings (yellow).

Return to the Navigation Blog

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch