December 2021 - Navigation and Mountain Weather

by Nigel Williams

The mountains influence their weather of course. With the Lapse rate around 2º cooler for every 300m of ascent, wind speeds tend to treble from the valley floor to the mountain top, and at least twice the precipitation can be expected on the summits. The monthly mean air temperature in Fort William never goes under 0º. On Ben Nevis, just 4 miles away, it is below freezing for 7 months of the year. The lapse rate varies between around 7 - 10 degrees difference between the two locations depending on the moisture content of the air. Fort William gets around 80 inches of precipitation annually, the summit of Ben Nevis around 170 inches. There is a plus side though - no midges on the top of the Ben.

The Mountain Weather Information Forecast (MWIS) always places the Munro height wind speed first in the list of weather information. This is because it will have the most impact on your day from route planning and navigation decisions to clothing and equipment. Plan to keep it on your back going uphill or on exposed ground, keeping off the ridges or to the lee side of them as much as possible.

Precipitation and temperature have rather more impact on your choice of equipment and clothing, although the impact of rain or sudden winter snow thaw on rivers can create navigational decisions and challenges. Clearly, a cool sunny autumn day in Fort William may require full waterproofs, ice axe, crampons, goggles etc on the Ben summit.

It is quite easy for a confident navigator to take direct routes up and down steep grassy slopes. These are often terraced, a natural slumping of the hill side into little parallel steps. In the autumn when the first snows arrive it is not uncommon to look up the slope and it looks largely green despite snow lying on each little terrace, and ascent is quite straight forward. However, when considering returning down the route, possibly because the daylight has shortened the day, the slope from above looks decidedly wintery and can carry significant risk of a slip or tumble.

Another aspect of altitude combined with a low pressure system I have experienced on several occasions has been a relatively small bubble in a compass expanding and really making it very difficult to maintain a bearing. It is frustrating, because on the tops in poor weather (which is usually associated with a low pressure system) is exactly when you most need accurate compass work.

From the wind direction forecast it is possible to estimate direction of travel across open country summer or winter.

In winter, with snow on the ground, the wind can give us quite a few directional clues. I have walked confidently, without bothering with a compass, towards a familiar flat topped summit in a white out. After about 5 minutes of thinking I must almost be at the cairn I came across some footprints in the snow at right angles to my direction of travel. It took me a few steps following them, assuming they would lead to the summit, before I realised they were exactly identical to my boot prints. Of course, I realised the relatively gentle wind had not been from a constant direction on my face. To make matters worse I then realised I had absolutely no idea where I might be in order to take an accurate bearing to the summit.

Similar information can be gleaned from Sastrugi, rather like mini sand dunes resulting from the funnelling of wind through cols, or where footprints have compressed snow and are left behind after wind strips away the softer snow. The steeper side is the windward side. Cols can be notorious for funnelling wind and giving quite a false direction.

Cornices are a similar feature of wind, creating an overhanging lip of snow that grows out in the same direction of the wind above cliffs or steep ground in the lee of the wind. These are navigationally a significant hazard should we stray too near an edge in a white out. In addition, the slopes below them are often avalanche prone areas.

These are examples of where the weather can be useful, but terrain and hazards can suddenly dictate our direction of travel and navigation skills, which in winter need significantly more experience and confidence.

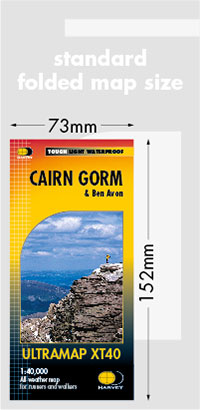

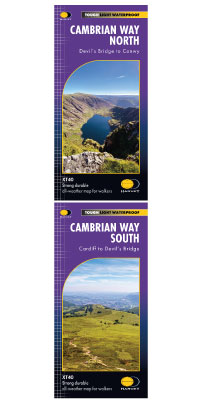

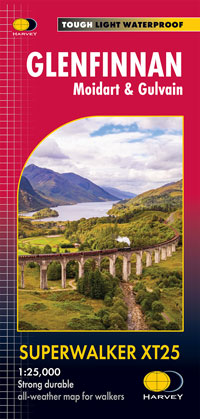

HARVEY British Mountain Maps, made in conjunction with the British Mountaineering Council (BMC), are a great aid to confident and sure navigation. Click to browse the full series.

Return to the Navigation Blog

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch