How good is your sense of direction?

by Nigel Williams

Santa Barbara Sense of Direction Scale (SBSOD)

You can read more about this study and test yourself - the background, the test and the scoring (it just takes 5 minutes) can be found here.

It was developed by correlating participants' self-reported sense of direction against their results of practical navigational tests and proved to be fairly accurate; it is now a widely used tool in navigation research. (On the scale of 1-7, I scored 5.6).

Our ability to make mental maps and navigate seems to be linked to our freedom and willingness to explore during the first decades of our life. In cultures where both men and women are encouraged to explore and play a part in hunting parties (for example, the Tsimane indigenous community in the Bolivian Amazon) there appears to be no difference in navigational abilities.

There is also evidence that for people with significant spatial awareness difficulties there is a hereditary element to their poor cognitive navigation. In 2009 this became a recognised condition Developmental Topographical Disorientation sometimes referred to as directional, spatial or geographic dyslexia.

Most of us are generally good at being able to remember routes we have travelled a number of times. We can estimate the distance and time travelled and picture in our mind the sequence of landmarks that we will see along the way. The much harder ability to acquire is known as "survey knowledge". This is the ability to mentally plan short cuts between two nearby routes in our cognitive maps, being able to accurately point to known landmarks related to those routes but which are not visible from our current position, and also an ability to sketch a reasonably accurate map of the routes. Testing route and survey knowledge can provide a measure of our ability to create accurate mental maps.

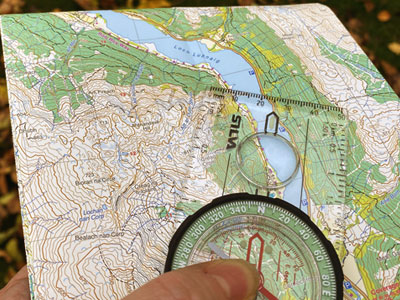

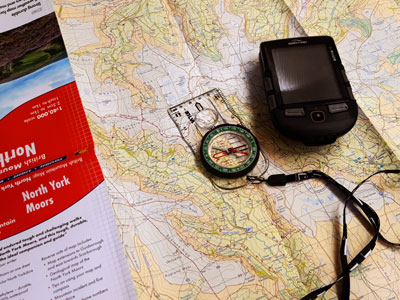

The GPS draws our attention away from landmark observation, absorbing the relationships between landmarks and our relative position to them as we travel. It also removes our decision making and learning from errors which often leads to further exploration, even though it may be unwelcome at the time. With an in-car GPS our navigation is more based on auditory information instead of observational information which is not how we navigate in the outdoors.

The GPS is a really useful navigational tool, the issue is when and how we use it in conjunction with our cognitive navigation and more traditional tools of map and compass.

Return to the Navigation Blog

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch