Navigating and safety in winter

by Nigel Williams

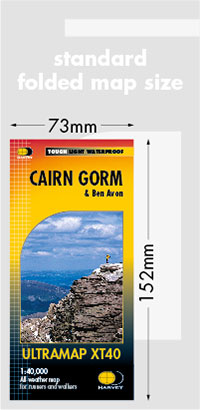

The higher we go in the UK at any time of the year the colder and windier it gets and the greater the amount of precipitation, usually snow in winter. The average daily windspeed on the Cairngorm plateau in winter is around 40mph. Although the summit of Ben Nevis is only 4 miles from Fort William, it receives only 2/3rds of the sunshine, just over double the precipitation, and is on average 8.5 degrees colder with it rarely going above 0º degrees during the winter months, and winds will be 3 times stronger. It's not enough to be able to navigate, we need to be able to do it sometimes in very difficult conditions when the right equipment and clothing are also of paramount importance.

Being in the cloud and on snow creates a whiteout effect, it feels a bit like walking inside a giant ping pong ball: there is no horizon line, blade of grass or boulder to aim toward. Many of our hill and mountain tops can be remarkably flat with low stone wind breaks on the summits that can be completely covered and difficult to locate, even in good visibility.

Navigation in poor winter visibility is almost entirely based on reading the contours and relying on compass and pacing skills. Observation which is so critical to the novice learning to navigate in the summer becomes almost irrelevant. What takes over is feeling the slope and referencing the angle you feel you should be crossing the slope. Straight up and down are easy to determine, but 30 or 50 degrees off that line is trickier. Long distances over about 1km need to be broken down into shorter legs, the choice of intermediate points to help keep one on track are critical. Using changes in steepness and aspect (the direction a slope faces) are invaluable. There is another useful tool in winter when combined with map and compass and that is the altimeter. It can help you traverse a slope accurately, locate your position especially if you are on a linear contour feature such as a ridge line, spur or broad gully. It can help with strategies to avoid avalanche risk and the risk of going over cliff edges and cornices.

Pacing in summer compared to winter is likely to be different and a relatively gentle up hill slope in fresh snow can significantly distort distance judgement doubling the number of paces needed to cover a 100m. I allow for this by looking at my footprint in the snow. I usually do 60 paces to 100m in summer on the flat. The distance between the heel of the front boot and toe of the rear boot is roughly the length of my footprint. Half the length of the footprint will be 90 paces and heel to toe will be 120, not unusual on a gentle up hill in soft snow. In winter due to the lack of features one may have to pace for distances around 700m which begins to build in errors. In summer maybe half that is usually possible between features and they are of course visible on the ground.

Avalanche risk is dependent on a number of factors primarily wind direction slope aspect, angle and altitude. Temperature changes and long-term temperature influences are also relevant. A big thaw followed by a refreeze is what stabilises a slope. It is often said that most avalanches are caused by their victims' poor decision making.

The met office weather forecasts are reliably accurate and can even cover individual mountains enabling realistic planning. The avalanche forecast is not as accurate, they only cover the most popular winter climbing areas so a good degree of interpretation is required for a chosen mountain walk. It should always be borne in mind that these are forecasts and are never guaranteed. If the wind direction or temperature at a certain altitude is inaccurate then the avalanche forecast is also likely to be inaccurate.

The Mountain Weather Information Service (MWIS) puts the wind speed first in their forecasts. Cold and precipitation although unpleasant don't stop us travelling but wind will. Wind tends to strip the snow off ridges and spurs so they can offer sensible routes free from avalanche risk but can end up with cornices if the sides of the ridge drop off steeply. In good visibility these will be obvious but in poor visibility it is important to keep well away from the edge.

Ski goggles are the most essential piece of kit you can't do any navigation in a blizzard without them. To manage intricate map and compass processes with gloves on, turn your back to the wind, kneel down on one knee and use the other knee as a stable base.

Navigation skills need not be a barrier to enjoying the mountain tops. Do the research and make realistic decisions about the route and weather conditions, and as with all things in the hills steady progressions will build solid experience.

- If you are in need of a compass then we stock a great range of items and other useful navigation equipment, suitable for all levels of navigation.

- For the perfect lanyard to go with your compass, the HARVEY Map - Measure - Go! scale bar laces double up to make measuring distance easy! Available in two scales, 1:25,000 scale markings (red) and 1:40,000 scale markings (yellow).

Return to the Navigation Blog

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch