Navigation stories for 2024 and beyond

by Nigel Williams

One is some research by the Scottish Mountain Safety Group that is looking into the reasons behind mountain accidents resulting in rescue team callouts. The other is analysis and potential further research coming from the "Sea Hero Quest" and the spin off "City Hero Quest" study into the loss of spatial awareness and our ability to navigate as an early indicator of dementia.

The number of team callouts across the UK are rising and placing huge pressures on the 70 or so volunteer teams across the UK. The number of people heading outdoors is also increasing on the back of various initiatives such as OS "Get Outside", the Covid lockdown bounce back, etc. One might expect technology being able to pin point our location would have resulted in less callouts for lost walkers, but this doesn't seem to be the case.

According to the 2022 Scottish Mountain Rescue review there were 330 callouts in Scotland related to mountaineering, of which 69% were summer hill walking, and 28% were winter hill walking. Trips and falls are the single biggest reason at 122 incidents, next is being lost (56), navigation error (43), reported missing (22), overdue (21) and technology reliance (7).

There will be other incidents related to navigation but each callout is given a single reason within the statistics. A navigation error early in the day may later lead to being out in the dark without a torch, and ending up breaking an ankle. The call out is likely to be recorded as a lower leg injury, but it could be recorded as a navigation error, or being poorly equipped. Issues to do with navigation would appear to account for around 50% of callouts.

In his 2007 report for sportscotland on "Scottish Mountaineering Incidents" Dr Bob Sharp comments on the high-proportion of call outs linked to poor navigation skills.

"Just over 50% of rescues involve searching for people who are lost or overdue. In most cases the people involved are not injured".

And later in the paper; "Greene (1996) noted that many walkers were not confident in their own navigation skills and Sharpe's survey of outdoor course providers also revealed navigation to be the central concern. They suggested that weak navigation and the inability to apply basic map and compass skills was a problem for a wide variety of groups and that there was a need for improved education in the subject (Sharp, 2001b; 2002). The Welsh study noted earlier (Jones, 2006) also identified poor navigation as a key factor behind mountain incidents."

So 17 years on, little seems to have changed; the messaging from MR continues to be to carry a map and compass and know how to use them and is often referred to as map reading rather than navigation. Ordnance Survey continue to talk about "map reading" and National Map Reading Week, with a disregard for the impact terrain has on the navigation skills required. These actions have not addressed the fundamental issue of "improved education" when referring to navigation skills in the context of recreation.

Orienteers are the most successful recreational (sport) navigators and, along with the National Navigation Award Scheme, which is primarily focused on walking, have each designed step by step navigation training programmes linked to steady terrain progressions; and they have tutor training and supporting documentation which would support improved education.

SNH (now NatureScot) did some research around 20 years ago and found that 73% of the walkers surveyed did not want to leave the path. Interestingly this is borne out by the 2022 MR report stating that "most incidents occurred near a path of some sort". This indicates the level of skills beginners really require, and it is not full compass bearings which can appear complex to a beginner as well as being out of context for their needs of simply deciding which path to choose; they are not having to decide and follow a compass direction.

However, if the powers that be decide to embrace a changed approach, the challenge will be: how do we engage and train the thousands of enthusiastic and well-meaning volunteer trainers and teachers? Similarly, how do we alter the public's perception of navigation and encourage the priority of traditional skills in addition to the phone (rather than instead of)? People will need evidence to convince them of the need for change.

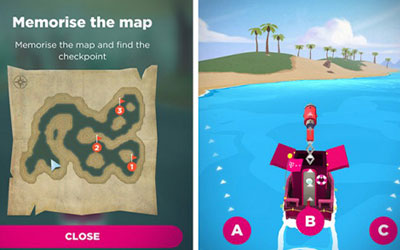

This is where the Sea Hero Quest research is relevant, because it is based around a series of 3D navigational challenges. It is a citizen Science research project led by professor Hugo Spiers at the Institute of Behavioural Neuroscience University College London and the University of East Anglia. It was available to anyone in the world and could be downloaded and played on a phone or tablet. Over a period of 5 years (it has finished now) data was collected from over 4.5 million participants from 37 different countries. It is estimated it would have taken 14,000 years to gain that quantity of data using traditional lab methods.

What this research is revealing is our differences in spatial awareness and navigational ability based on factors such as where we were brought up, our age, gender, ethnicity and education level. What was also clever about this approach is that it involved decision making (albeit without consequences) but it is non-verbal. This is another subtle element of teaching navigation skills, much of the traditional approach requires people to give verbal directions in the form of accurate numbers which can be scrutinized. A more supportive approach is to just ask people to point and head off as we would if on our own.

Eye tracking technology is also providing an insight into our focus when walking and how it might impact our decision making. It could also provide evidence to support the use of orienteering scale maps with more detail close to the path than traditional map scales for walkers. This would help beginners gain both terrain and mapping confidence.

The solutions are already out there, but we may continue to struggle to reduce the number of call outs for navigation related incidents if we fail to consider both the teaching approach and messaging to the public. So, I am hopeful that 2024 may be the start of change and that with research supporting it the big players in this field will be persuaded to properly review and improve education for recreational navigation.

Return to the Navigation Blog

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch