Have we lost the instinct of spatial awareness?

by Nigel Williams

Every living creature has some sort of navigational skill in order to find food, escape danger and reproduce. The range of methods employed include vision, sun, moon, polarised light, stars, scent, touch, electric fields and the Earth's magnetic fields. Many animals use a combination of these and appear to have some sort of memory, or innate knowledge, enabling them to return to food, or the safety of the nest, and work out detours around blockages in their path. Bees, for instance, have even been filmed communicating directions and distances to flowers to the other bees in their hive.

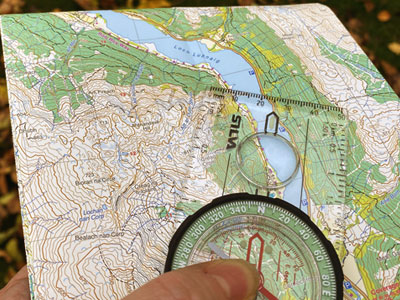

Human beings have taken navigation, and the communication of it, to a different level, in that we have created maps in various forms and also the compass, to help us use the Earth's magnetic fields. There have been experiments that indicate the possibility that humans might at one time have been able to sense the Earth's magnetic fields. Perhaps, as humans began to create basic tools, we evolved other cognitive navigation skills and lost the need for the magnetic guidance.

In the past few years non-invasive ways of accurately tracking brain activity down to a single cell have revealed secrets of the neurological pathways that humans have developed over 400,000 years.

There is also evidence that socio-economic circumstances create different outdoor exploration opportunities, which impact people's development of spatial perception, but not necessarily their capacity. For example, parents tend to be happier for boys to go off and explore the local neighbourhood than for girls. Yet, given the opportunity, we are all hard wired to be able to use spatial information and find our way around.

Our brains are all programmed to receive and store geographical information but we need to download it and to exercise the neural pathways. London Taxi drivers develop a larger than normal hippocampus because they have to learn and recall thousands of routes and be able to work out ways around blockages. It is not the same for London bus drivers, who drive similar routes day in day out; their hippocampi do not grow in the same way as those of the taxi drivers.

Research is beginning to demonstrate a possible impact on the formation of our spatial perception caused by habitual use of digital technology in cars, phones etc. Use of these devices for all our navigation needs from a young age removes that process of observation and recording of landmarks; it bypasses the pure outdoor exploration without a map or compass that our ancestors would have experienced. There is mounting evidence that, in tests, people who rely on these devices have poorer spatial awareness than people who use other forms of navigation. The reason seems to be because digital media and GPS utilise different neural pathways that do not feed the hippocampus to create our map memory.

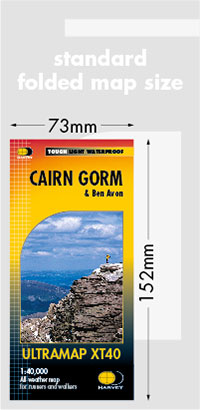

The general public have only had access to accurate maps and compasses for recreation in the past 100 years, spurred on by their use during both world wars. If anything, that may have enhanced our awareness and encouraged us to explore further and look for landmarks around us.

The world of digital navigation is little more than 20 years old. No one knows if 400,000 years of neural advancement can be done away with nor whether we will evolve other processes to compensate. However, it is startling how, in a tiny fraction of time, humans have invented a device that can disrupt such a fundamental part of one of the most basic human skills that has enabled our species to survive and thrive.

Return to the Navigation Blog

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch