What to do when completely disorientated or lost

by Nigel Williams

When Ordnance Survey commissioned some research in 2022, of the 2000 people questioned, more than half (56%) of walkers admit they've gone astray because they can't use a map or follow an app correctly, with 39% resorting to calling friends and family, 26% flagging down help, and 10% reporting calling upon mountain rescue services to get home.

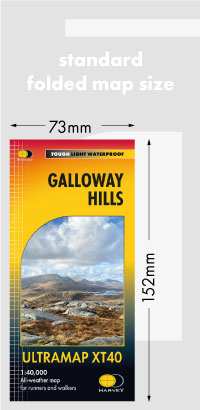

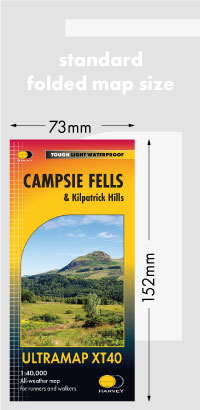

We also know that around 75% of people do not want to venture off a footpath. However, not all paths are well marked. Much can depend on the scale of map being used, as well as the last survey and production date.

I once came across a recently planted fir forest in the Lomond Hills in Fife which caused a certain amount of head scratching as to where we could be. I remembered that fir trees grow a layer or whorl of branches each year. We counted up the trunk about 10 whorls indicating the plantation was around 10 years old and then found that the map had been produced 12 years previously, and last surveyed a couple of years before that. The date on a map can be more useful we realise.

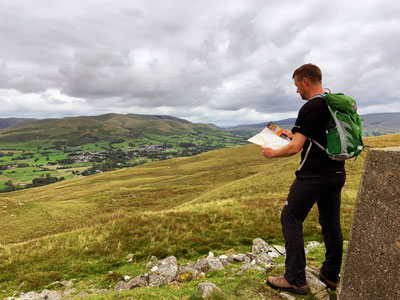

Perhaps we are able to locate our position with a little "move to prove"; just heading 50 - 100 metres in different directions to get better views of our surroundings and identify a land mark or two to confirm or prove our location. We then realise we are way off route and completely missed a path junction a couple of kilometres back.

This is the next critical decision point. It is not uncommon to decide backtracking is too much of a detour, and instead choose to head cross-country, away from a path, to get back onto the planned route. This is when not just map and compass skills may be needed, but a good appreciation of contour information and navigation strategies as well. We may end up digging a deeper hole for ourselves, especially if the light is fading or weather deteriorating.

One of the problems is that if we become stressed, neuroscience research suggests there is a tendency towards increased risk-taking, going for the cross country option rather than backtracking to where the path provides an easy to navigate handrail despite a longer distance and time.

If we are really stressed the neural pathways to our map memory and sound navigation decision-making become blocked, and our behaviour erratic; fright and flight may kick in, which is likely to make matters much worse.

Controlling our panic level is really important if we want to start to try to resolve the problem. Stop, sit down, have something to eat and drink, set and study the map, listen for running water, think about your last known position and how far and in what direction you might have come and what you have seen. I'm not particularly a fan of acronyms but some people suggest DDCRAPS as an initial thinking process to analyse their potential location. Some argue it helps to focus the mind away from the stress of the situation. Direction, Distance & time Conventional signs, Relief, Alignment, Proximity and Shape. This is very much a static process at the end of which we may be none the wiser. Eventually we will need to travel to find or confirm a definite location but we need to do that with a logical plan.

If lost in a largely flat moorland or plateau area with no linear feature around, consider the big picture, choose a direction to head in that might bring you to a linear feature, stream, edge of wood, cliff edge (not in winter) etc. However, if you are on a significant slope, check which direction it faces - slope aspect. If it faces north we can eliminate all the possible slopes on the map facing E, S, or W. This gives an approximate AREA we could be in and will help us choose the direction to head to find a LINE feature.

Once on a line feature, a stream for instance, take a bearing along it to check the rough direction it runs in, north - south perhaps. It may be that there are several options of stream with that orientation.

Study the map for a different recognisable POINT in each of the streams e.g. one has a significant bend, the other has a significant junction with a stream coming in from the E. Follow the stream until one of the points is identified. That should enable confirmation of our position. Now we require a safe plan to get back on route or to the car.

Return to the Navigation Blog

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch