Why do people get lost in British hills?

by Nigel Williams

When OS did a survey in 2022 of two thousand walkers, more than half admitted to having been lost at some point. In many cases it appeared their interpretation of map symbols, including contours, was poor. A lack of basic navigation skills with map and compass was another, as was the decision on which are the appropriate mapping and navigational tools to use, including the phone, Google maps and GPS. The environmental vulnerabilities of the device make it a poor decision if it is the sole navigation tool.

Poor observation and information-gathering along the way to ensure timely decision-making (usually at a junction) was never mentioned in the survey. Yet this is easily overlooked when one is having a good blether and subconsciously just keeping to the most obvious looking path on the ground. Navigation puts a heavy load on the brain so it tends to be easily distracted to less onerous work. Consciously maintaining a focus on the navigation task, along with having the tools of navigation easily to hand rather than buried in a rucksack, also plays a part.

Poor decision-making to rectify an initial error of observation can result in a decision to try a shortcut across country, which is a mistake. The moment one goes across country the navigation and decision-making requirements can multiply exponentially compared to following linear features and retracing one's steps on the path, as advocated by AdventureSmart for instance. www.adventuresmart.uk

Neurological research suggests we develop most of our cognitive navigation ability in the first 20 years of our lives - it then plateaus before deteriorating fairly rapidly in our old age as we become sedentary. Our ability is influenced by how much we practise, which impacts our confidence; two key elements of successful navigation. We know from research into London Taxi drivers training, and veteran orienteers - neither of which use a GPS - that practising navigation can help us improve or maintain our cognitive navigation ability.

In summary, observation and navigation decision-making play a significant part in preventing us from becoming lost. These are not technical compass skills so they are often overlooked in navigation or map reading teaching. And, ironically, they are the two things that habitual use of the GPS overrides. Behind the more obvious reasons for becoming lost there is the influence of our early years' spatial development, but it is never too late to learn the simple skills of outdoor navigation.

- If you are in need of a compass then we stock a great range of items and other useful navigation equipment, suitable for all levels of navigation.

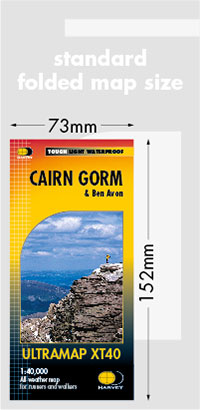

- For the perfect lanyard to go with your compass, the HARVEY Map - Measure - Go! scale bar laces double up to make measuring distance easy! Available in two scales, 1:25,000 scale markings (red) and 1:40,000 scale markings (yellow).

Return to the Navigation Blog

FREE UK tracked delivery

FREE UK tracked delivery Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch

Order by 12pm Mon-Fri for same day dispatch